Susan Bayly in 1983, reviewing Caste Conflict and Elite Formation: The Rise of a Karava Elite in Sri Lanka, 1500-1931 by Michael Roberts Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1982.

Susan Bayly in 1983, reviewing Caste Conflict and Elite Formation: The Rise of a Karava Elite in Sri Lanka, 1500-1931 by Michael Roberts Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1982.

The literature on the south Asian caste system is vast and contentious and the current war of words shows no sign of abating. This book conforms to current trends both in focusing on the experience of a single caste group under colonial rule, and also in adopting a polemical tone towards other historians. Roberts’ subject is the Karava population of Sri Lanka and his first aim is to explain why this group of poor fishermen and artisans managed to throw up a disproportionately large elite of businessmen, lawyers and other western-educated professional men by the end of the nineteenth-century. The discussion is set against the background of works on comparable Asian business communities such as the Marwaris and Parsis. An important theme, then, is the relationship between individual enterprise and the corporate structure of caste: did the Karava magnate class emerge because of, or in spite of, their roots in a hierarchical caste order?

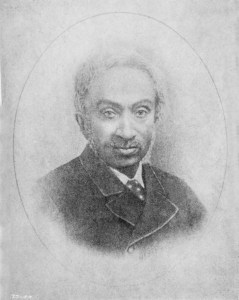

Jeronis de Soysa and CH de Soysa

Jeronis de Soysa and CH de Soysa

The conclusion here is that caste did not debar individual mobility and enterprise as the conventional wisdom once held, and that like other south Asian trading groups the Karava were able to use caste and kin networks to recruit labour and transmit capital, contracts and market information (pp. 127-30). The Sri Lankan setting provides a useful vantage point. Weber of course was the first to suggest that in Hindu society entrepreneurs were often outsiders-Zoroastrian Parsis and Jains-or that they held low caste status. Roberts shows that the same pattern applied in Sinhalese Buddhist society. As fishermen the Karava violated Buddhist sanctions against taking life; they, too, overcame the handicap of low status and a polluting occupation, moving from fishing to profitable new trades.

Roberts argues that the Karava were able to turn their traditional skills to advantage in an expanding colonial economy. He traces their association with trade back to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries when Portuguese and Dutch rule helped to create a demand for commodities and services which the Karava were particularly well equipped to supply. As fishermen many of them moved easily into ship-building and other waterfront industries in the new colonial port towns, and their skill in building fishing boats enabled them to take up carpentry and other trades patronized by Europeans. For some Karava the next move was into petty contracting and during the seventeenth century enterprising members of the group supplied timber and construction materials to the Dutch. Others engaged in those well-known standbys of low-caste ‘new men’, distilling and arrack renting (pp. 79-89).

South Asian fishermen have often been especially mobile people. The Tamil Paravas are another group who first built up capital as fish dealers and then moved into more lucrative trades. And like the Marwaris and south Indian Tamils who abandoned their homelands for greener pastures in the Ganges Valley and Ceylon respectively, many Karava found prosperity by moving into the interior from their homes on the Sri Lankan coast.[1]

The most successful sections of the book are those tracing the rise of Karava entrepreneurs who began as pedlars and itinerant artisans during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and later speculated in Highland plantation property. Roberts notes that in Ceylon the expansion of the market economy enhanced rather than undercut opportunities for trade and investment by non-Europeans. In contrast to Indonesia and India, Asians were well represented among plantation proprietors in Ceylon and nineteenth-century Karava businessmen owed much of their success to British sponsorship of coffee, tea and coconut plantations in the hinterland. Roberts’ case studies of Karava magnates are a real contribution to our understanding of Asian trade and the growth of the colonial economy in Ceylon. His discussion of the Warusahannadige de Soysas for example shows how this family of parvenu merchant princes rose through their success as pioneer investors in the Central Highlands, building up business and marriage alliances among other Karava practising the same style of thrusting entrepreneurship.

The de Soysas controlled a great web of urban property holdings, as well as oil mills, mines and factories by the end of the nineteenth century. And they were not unique. By the middle of the century the majority of Ceylon’s arrack and toll renters were Karava and by 1917 over half the plantations held by Sinhalese were under Karava proprietors (pp. 109-112). This picture of wealth and power is completed with an account of the Karava elite’s success in acquiring English education qualifications and the proliferation of Karava doctors, teachers and lawyers during the later nineteenth century.

Susew de Soysa

Susew de Soysa  Alfred House in the mid 19th century

Alfred House in the mid 19th century

If the book had been limited to a study of the Karavas’ commercial exploits and the relationship between caste and entrepreneurship it would have been quite successful. But Roberts has more ambitious aims. His concern is not just with the Karava notables but with the group as a whole and its place in the Sinhalese caste order, and it is here that problems arise. For one thing the writing becomes clogged with turgid sociological jargon as Roberts turns from his treatment of Karava businessmen and moves on to wider issues. Thus we are told that ‘the transformative potential of Karava wedge marginality crystallised itself yet further’ (p. 291) and that

‘ … the analytical approach has been eclectic, and sometimes even syncretic. However, in the final chapter this eclectic approach is diluted and the lines of analysis are sharpened so as to emphasise those factors to which greater causal weight is attached on the basis of an essentially intuitive and qualitative assessment (pp. i6-i7).’

A strong-minded sub-editor might have improved the style, but more fundamental problems remain. These arise from Roberts’ understanding of the caste system itself, and since much of the book is taken up with a review of current works on the politics and history of caste, it will be helpful to examine his treatment of the caste system in relation to other recent studies.

Caste is a minefield for the historian, but some recent treatments of castes and their historical development deal more convincingly with the subject than Roberts does. Frank Conlon, for example, tackles a theme close to Roberts, the growth of corporate identity among one Hindu caste, the Chitrapur Saraswat Brahmin[][2]. It is now recognized that castes are not static formations born at some time in the remote and unknowable past. Conlon’s work on these Brahmins from Kanara is a particularly successful study of ‘caste formation’. It breaks new ground in its use of records from a powerful math (monastic institution) and shows that the group’s caste identity was built up around their allegiance to a line of swamis or spiritual preceptors based in the math from about 1700. Other factors also helped to mould their identity particularly patronage from local rulers.

One of the strengths of Conlon’s book is the way that it portrays different stages in the Saraswats’ evolution from 1700 to the 1930s. We are shown that a caste’s sense of affinity could take on many different forms ranging from loose, impermanent attachments to a more definite and structured sense of com- munity. “The separateness of the Saraswats cannot be spoken of as a rigid, unchanging concept, but rather as a tendency of an identity to inhere in certain families who subsequently joined to form what is known as the Chitrapur Saraswat Brahmin jati (p. 6).”

Conlon also shows that caste bonds can be temporary. The Chitrapur Saraswats’ medieval ancestors seem to have emerged from the sub-divisions of a separate Brahmin caste cluster based in Goa. In describing. the process of addition, subtraction and incorporation over time which produced Conlon’s particular caste group he argues,

“The classical definitions of caste do not easily accommodate the full range of possible fission and fusion processes which lie in the background of what at a given moment may be seen as a unified and clearly bounded group (p. 8).”

Roberts’ approach to the question of the Karavas’ origins is quite different. He insists that the Karava possessed a ‘solidarity’ and ‘primordial identity … inherited from the past’ (p. 212). The contrast to Conlon’s treatment of caste formation is all the more conspicuous since the Karavas’ beginnings are far more obscure than the Saraswats’. Roberts’ people seem to have been migrants from south India, but it is not clear how they were related to the Malayalam- speaking Mukkuva fishermen or Tamil Paravas whom they resemble, or when they arrived in Sri Lanka, or how they broke away from their mother castes and began to speak Sinhalese. Although he begins by saying that the Karava and other migrant groups only ‘appear to have had a sense of distinctiveness’ by the sixteenth century (p. 25), they are described throughout as fully fledged ‘communities’. Compared with Conlon’s subtle and cautious approach to caste formation Roberts presents little more than an unsupported assertion that the Karava were a community and that they possessed this almost mystical sense of ‘primordial identity’.

If Roberts’ account of the Karavas’ origins has its deficiencies, there are even greater problems in his understanding of the caste system itself. In his view the essence of the caste system is conflict between competing interest groups. High and low castes are pitted against one another over many centuries. The language is highly charged: there are ‘caste fears’ (p.174), ‘caste friction’ (p. 96) and even ‘caste warfare’ (p.163) as well as ‘“native aristocrats”’ maintaining low castes ‘in a downtrodden condition’ (p.64). The Karava and the other low-country migrant castes ‘were part of, or becoming part of, a structure of discrimination‘ (p.66).

Roberts does mention other studies which treat caste as much more than a ‘structure of discrimination.’ He acknowledges Leach’s view of Hindu caste relations as a system of interdependencies and notes that the Sinhalese castes made ritualized exchanges of service which resembled Indian jajmani networks (PP- 35, 47). In spite of this, he still portrays caste as a kind of social conspiracy. When Karava and high-caste Goyigama clash over their standing in a ranked caste census compiled by the British this becomes ‘part of a Goyigama strategy to degrade the Karava’ (pp. 60-1) and ‘a case of attempted murder by classification‘ (p. 56). The problem is that this dramatic language obscures more than it explains and offers value judgements in place of objective analysis. The caste system may offend present-day egalitarianism but even so there is more to caste than oppression or the use of ideology to maintain the authority of dominant castes.

What, then, is the alternative? Some recent works have argued that it is time to move beyond the individual caste as a unit of study and look at other institutions which shed light on local societies as a whole. In their work on Hindu temples Carol Breckenridge and Arjun Appadurai have described complex ‘honours systems’ which operate in south Indian localities[3]. They have emphasized that ritual status is negotiable in Hindu society, that the standing of local caste groups is open to constant challenge, and that readjustments in the local hierarchy commonly take place in the course of temple ceremonies. In this view temple festivals (utsavams) should be seen as a series of ‘honours’ or ritual privileges. The allocation of ‘honours’ such as the right to make particular offerings to the deity serves to confirm or redefine relationships of precedence and ritual subordination within the society.

The difference between the Appadurais and Roberts here is that the idea of the honours system allows for solidarity as well as stratification in the caste system. Low caste groups may jostle for a higher place in local ranking schemes but at the same time they and every other group have a stake in the utsavam; it is a corporate event offering a measure of prestige and the hope of advancement to all who take part.

The allocation of local honours is often contentious, and south India is famous for riots and ‘honours disputes’ during festivals. But this is not the same as Roberts’ notion of ‘caste warfare’. These conflicts are an integral part of the system and local schemes of precedence are generally flexible enough to accommodate continual reshuffling. Roberts would have us believe that when bodies of Karava fought with other groups over caste titles and other symbols of rank during the nineteenth century they were rejecting hated tokens of subordination and seeking to throw off what he calls caste ‘disabilities’. The problem with this is that these conflicts are so hard to distinguish from the well-established pattern of Indian honours disputes. Certainly, in south India lower caste groups like the Nadars and Izhavas did not seek to ‘throw off’ or escape from caste. Instead, in the famous breast cloth and temple entry campaigns they accepted a symbolic vocabulary which was common to all local groups and sought to manipulate it to their own advantage[4].

Michael Moffatt’s work on south Indian untouchables also supports this idea of a common vocabulary and common values linking different caste groups.[5] Moffatt’s Paraiyans have even lower caste status than the Karava, and yet he has found that they are part of a ‘fundamental cultural consensus [which operates] from top to bottom of a local caste hierarchy’ (p.4). Like the Appadurais, Moffatt allows for conflict and stratification within local caste systems: his untouchables are excluded from some (but not all) of the ceremonies performed at village shrines, and yet they do not possess a separate sub-culture. Where they are excluded from these corporate village rites they replicate the observances of the wider society together with the beliefs which engender them. Thus Moffatt too, rejects the idea that lower castes are an oppressed underclass who react to their ‘disabilities’ by becoming ‘detached or alienated’ from the system[6]. Their gods, beliefs and rituals are ‘identical to those of more global Indian village culture’ (p.3); they do not question the legitimacy of the caste system as such; and the local goddess festivals in which they have rights or ‘shares’ serve to integrate them into the ritual life of the village.

Roberts’ approach throws up further difficulties when we move into the nineteenth century. He seeks to show that by the end of the century Karava magnates and professional men found themselves in a position of ‘status inconsistency’– rich, increasingly well-educated and yet still treated as inferiors by the upper caste Goyigama. According to Roberts, the Karavas’ response was to engage in a ‘status battle’ (p. 133), a campaign to ‘contest the validity of the prevailing caste hierarchy’ (p.10) and claim ‘caste primacy’ over the Goyigama.

Here we are on familiar ground. Many scholars have dealt with what Roberts calls ‘caste mobility’ in India and M. N. Srinivas contributed one of the essential (now much-modified) concepts to the subject when he coined the term Sanskritization][7]. Other works such as those on south India by Hardgrave and Jeffrey have studied the pressure groups known as caste associations and have portrayed them as an important departure in the historical development of caste[8]. They see these bodies as broadly-based mass movements among low castes who sought to break out of the ‘discriminatory’ caste system,and were galvanized into launching their protests by new wealth, education and exposure to western egalitarian ideals.

D. A. Washbrook and G. J. Baker have challenged this approach, depicting many caste associations as no more than artificial coalitions cobbled together so that spurious caste ‘leaders’ could claim a mass following and gain political concessions from the British[9]. Roberts acknowledges that historians now have no excuse for accepting caste association propaganda at face value. Nevertheless, his discussion of the Karava owes much to the same studies attacked by Washbrook and Baker and comes to some of the same conclusions

Like Hardgrave and Jeffrey, Roberts begins from an assumption of cohesive caste ‘interests’ and united caste groups locked in combat with their rivals. In this case it is the Goyigama who are the Karavas’ ‘arch-enemies’ (sic). The Sinhalese did not in fact form caste associations but Roberts makes much of the fact that from about 1876 Karava and Goyigama pamphleteers pumped out scurrilous propaganda denouncing one another’s ancestry and ritual standing and asserting their own caste superiority. A few years later Karava lawyers and businessmen tried to seize a reserved seat on the Ceylon Legislative Council which had previously been held by Goyigama. From 1906 leading Karava lobbied for ‘constitutional reform’-i.e. for an increase in the number of Council seats so that a Karava stood a better chance of election.

Roberts sees both the pamphleteering and the political battles as a series of concerted moves, a ‘forward thrust’ by the Karava elite on behalf of the caste as a whole. During the nineteenth century Hardgrave’s Nadars (toddy-tappers turned merchants) produced similar self-glorifying caste pamphlets, and so too many Nadar magnates fought for political power bases comparable to the Ceylon Legislative Council seats. Roberts disagrees with Hardgrave only in arguing that campaigns of this sort did not create caste-wide consciousness but instead were the products of an existing solidarity. ‘They could not escape their Karava-ness,’ he declares (p. 212)

Thus Roberts would reject the notion that the Karava magnates were merely Washbrook-style ‘bosses’ vying for power and political spoils. He insists that the Karava notables had close ties with the wider Karava population and that even poor Karavas felt that their interests were served by having a Karava on the Legislative Council.

Roberts does show that there were closer links between Karava in different localities than were typical of many Indian castes. Therefore the social or political successes of leading Karava may have meant more to their caste fellows than did those of Indian magnates who belonged to looser and more heterogeneous castes. Even so he strains our credibility by depicting these would-be Karava power-breakers as community-minded ‘leaders’ and ‘spokesmen’. One feels the need of a little healthy scepticism here. Furthermore the attempt to provide a kind of cultural depth to the argument by linking the political campaigns to the pamphleteering is not very successful. It is not clear whether the two movements were actually connected. And while Roberts admits that the pamphlets had little practical impact — ‘it is doubtful if the ordering of castes in the popular view was much modified by this series of engagements‘ (p. I64)-it is this exchange of a few dozen pamphlets which he describes as ‘caste warfare’ (p. I63). Whatever was going on in Ceylon in this period was a far cry from the communal violence of north India or the honours disputes and left-hand:right-hand caste conflicts of south India, or even the 1915 Sinhalese-Moor riots in Ceylon which Roberts does not link to his Karava disputes.

In fact, the whole argument about inherent friction between castes in Sinhalese society rests on a series of unproved assumptions. The Karava and other low castes ‘must have been … aware of the overt marks of low status to which they were subject ...’ (p. 66). Goyigama victories in the 1924 Council elections ‘[conveyed] implications which caste-conscious contemporaries must have noticed’ (p. I74). And ‘the only individuals to resent such degrading attributes [as unflattering caste titles]’ would not have been the Karava ‘men of ambition’: ‘In certain contexts the ordinary Karava … was as likely to resent derogatory forms of address.’ (p. 210)

We then move from presumption to assertion. Since the Karava ‘must have’ suffered under these slights and discriminations they ‘must have’ been driven en masse to campaign against caste ‘disabilities’. The idea of collective resentments seems crude in the light of what is known about honours and exchange in the caste system. And if this fails then Roberts’ main argument about ‘Karava-ness’ becomes dubious as well, since he believes that the Karavas’ shared grievances against the Goyigama played a major role in moulding them into a community. Roberts uses this line of argument to launch an attack on Washbrook and Baker. Their view of the political history of south Indian castes is condemned for ‘misplaced concreteness’ and ‘sociological naivete’ (p. 194). In particular he rejects their critiques of Jeffrey and Hardgrave[10]. Washbrook and Baker argued that for most agricultural groups caste had little meaning outside the face-to-face society and could not provide a basis for political mobilization. Instead, Washbrook contended that it was the British who provided the stimulus for local caste clusters to claim wider regional links. Caste as a set of Presidency-wide groupings was no more than an ‘administrative fiction.’[11] The British drew up the Census and allocated political plums on the basis of caste. Local caste groups then made these British misconceptions self-fulfilling: they took up and manipulated the caste titles applied by the British and behaved as if they corresponded to the real operation of caste in society.

According to Roberts the broad regional caste categories described by Washbrook were not European inventions but authentic ‘cultural typifications’ (p. 197). What he appears to mean here is that south Indians possessed a clear understanding of what caste identities like Nadar or Izhava meant, and that these perceptions of caste identity derived from basic ideas and cultural symbols which were familiar to everyone in the society. These typifications became ‘infused with meaning’ in Roberts’ phrase through the influence of Hindu religious values.

Admittedly there is something in his complaint that Washbrook underestimates the role of religious experience in promoting the cohesion of certain castes, notably the Madras Komatis (p.203). And in contrast Roberts presents some interesting material on a nineteenth-century Buddhist ‘revitalisation movement’ which was patronized by leading Karava. This discussion also suggests a link between the commercial and ritual spheres as it was the Karava magnates’ trading contacts in Burma which gave them access to Burmese monasteries and teachers (p.260).

Even so, the agricultural castes of Kerala and Madras do not present a convincing picture of cohesiveness and caste solidarity. Roberts tries hard to enlist Jeffrey to his cause: on the claim for corporate unity among the Izhava toddy-tappers and high caste Nayars of Kerala we are told: ‘This evidence [in Jeffrey’s book] is rather subdued and inadequately stressed but it was there for any reader with sociological imagination to tease out’ (p. 194). In fact, Jeffrey’s evidence about ‘Izhava-ness’ is fairly thin however much it is ‘teased out’ and Roberts does not enhance his case by arguing that the Izhavas developed a sense of solidarity because of their ‘shared common disabilities’. He also claims the Nayars as a single caste group, thus disregarding the vast heterogeneity of the people who called themselves Nayars in the pre-colonial and colonial period-aristocratic warriors, cultivators, artisans, traders and even oil pressers of low ritual status. The Nayars are particularly inappropriate for Roberts’ purpose because the title Nayar did not denote a single tightly organized caste of Malayalis. It was a mark of professional standing accorded to any warrior whom the rajas of Travancore and other Keralan rulers recruited into their armies and was aspired to by many non-warrior groups as well.[12]

In fact, historic caste titles did not constitute the same sorts of ‘cultural typifications’. Many caste names served as the most general honorifics, mere assertions of status such as Jat, Rajput, Vellala or Pillai; others denoted highly specific occupations and ranks. They did not necessarily imply the exitance of any compelling or permanent communal identity.

It seems pointless, then, for Roberts to compare the Karava to the great amorphous agricultural castes of south India whose occupations provide no basis for cohesive organization, who have no craft skills to protect and no regional financial interests to channel along caste lines. The odd thing about Roberts’ work is that once we set aside all the sound and fury of the attack on Washbrook we are left with a remarkably similar line of argument. While he challenges the view of the British ‘inventing’ caste categories Roberts does acknowledge the role of colonial authority in building up caste institutions, particularly through the use of headmen of artisan castes to recruit labourers under the state’s obligatory labour system (rajakariya). Thus, the Karava clearly belong to the category of specialized caste groups- traders, artisans, priests-whom Washbrook specifically cites as castes with strong institutions and a sense of identity, in contrast to the agricultural castes.

Ultimately this reader comes away with the feeling that though studies of single caste groups like Roberts’ have contributed much to south Asian historiography, they are beginning to outlive their usefulness. Inevitably the central questions of ‘identity’ and ‘caste consciousness’ are begged when the starting point is a single entity. Perhaps the future lies with studies which seek to portray the evolution of relations between a variety of castes in the context of the wider field of economic, religious and political organization.

SUSAN BAYLY, University of Cambridge…………………………………. …. https://www.socanth.cam.ac.uk/directory/professor-susan-bayly

END NOTES

[1] See e.g. my article, ‘A Christian Caste in Hindu Society: Religious Leadership and Social Conflict among the Paravas of Southern Tamilnadu’, in Modern Asian Studies, 15, 2 (1981), pp. I 77-20I; and Thomas A. Timberg, The Marwaris–From Traders to Industrialists (Delhi, 1977).

[2] A Caste in a Changing World. The Chitrapur Saraswat Brahmans, 1700- 1935 (Berkeley, I977)

[3] ‘The South Indian Temple: Authority, Honour and Redistribution’, in Contributions to Indian Sociology (NS) 10, 2 (I976), pp. I87- 211

[4] Unlike some authors who have described low-caste mobility in India, Roberts does not claim that the Karava were trying to break out of the caste system itself, but were attempting to escape its ‘disabilities’ by adopting higher caste customs and privileges (p. 140). This is part of a more general argument that the Karava and other migrant castes were only partially ‘integrated’ into Sinhalese Buddhist society during the colonial period. He argues that they were undergoing ‘acculturation and integration’ into the Sinhalese social structure during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and that their effort to emulate the Goyigamas’ lifestyle was one of the signs of this process. One problem here is that if the Karava were an exceptional group, outsiders who were not fully absorbed into the Sinhalese social order even by the nineteenth century, then it is hard to see them as a general case which can be applied to a discussion of caste structure and ideology among mainstream Hindu castes in India.

[5] An Untouchable Community in South India. Structure and Consensus (Princeton, New Jersey, I979).

[6] See Moffatt’s discussion of works by Kathleen Gough, Joan Mencher and Gerald Berreman (pp. 9-24).

[7] This is the attempt by low castes to elevate their status by emulating the lifestyle of their caste superiors. See Srinivas, Caste in Modern India and Other Essays (London. 1970).

[8] Robert L. Hardgrave, Jr., The Nadars of Tamilnad. The Political Culture of a Community in Change (Berkeley, 1969); Robin Jeffrey, The Decline of Nayar Dominance: Society and Politics in Travancore, 1847-1908 (London, 1976).

[9] See, in particular, D. A. Washbrook, ‘The Development of Caste Organisation in South India I880 to 1925’, in C. J. Baker and D. A. Washbrook (eds), South India: Political Institutions and Political Change 1880-1940 (Delhi, 1975), pp. 150-203.

[10] Review by C. J. Baker of Jeffrey, The Decline of Nayar Dominance in Modern Asian Studies 12, 2 (1977), pp. 306-9; and review by D. A. Washbrook of Hardgrave, The Nadars of Tamilnad in Modern Asian Studies 5, 3 (1971), PP.278-83

[11] Washbrook, ‘The Development of Caste Organization,’ p.189.

[12] The traveller Francis Buchanan encountered ‘Nayar’ potters, tailors and palan-quin bearers. See A Journey from Madras through the Countries of Mysore, Canara and Malabar (Madras, 1807), vol. II, pp. 408-9. And the assimilation of ritually polluting Tamils into the Nayar caste category is described by L. K. Anantha Krishna Iyer in The Cochin Tribes and Castes (Madras 1912), vol. II, p.18.

Pingback: Caste in Sri Lanka and the Rise of the Karava: Meeting Susan Bayly’s Review in 1983 | Thuppahi's Blog

Read the article to the end. Intresting

Ranjan Rodrigo

Sydney.

It is now possible to get a better picture of history due to the advancements in science like DNA studies, archeology and epigraphy. Interestingly, the earliest reference to Karava is in the ancient Brahmi script from a site near the Abayagiri Viharaya. Witout going into detail about distant history, I bring your attention to the fact that some of the churches in the coastal regions were shrines before, these were however not usually ‘Buddhist’ shrines and were managed by the coastal clansmen discussed in this article. Though critical of Michael Roberts’ analysis, SUSAN BAYLY confirms some of Roberts’ arguments with descriptions of the competition for the temple honours (system) by caste groups.

The Washbrook and Baker argument that for most agricultural groups caste had little meaning outside the face-to-face society and could not provide a basis for political mobilization and that it was the British who provided the stimulus for local caste clusters to claim wider regional links was a factor exploited by the colonial appointed plums who at times even reinvented their identity as being from those groups.

The statement ”tried to ‘sieze’ colonial appointment into the legislative council” makes you wonder whether this was Susan’s original thought.

She is correct in her assessment that this was in the interest of family groups in power and/or those with ambitions, a facet observed by William Skeen in his 1870 publication ‘Adams Peak..’ which makes mention of actions and perceptions of an obstructive clique.

One could add as an example, the power relations between the educated (teachers, businessmen and other professionals) and the not so educated low country workmen (with capital) in the Kandyan region. Puran Appu and Gongalegoda married daughters of local headmen and were accepted as liberators and kings.

EMAIL COMMENT from KUMAR DAVID in Lanka, 12 August 2021:

“Thank you very much, whoever sent this to me. Yes it is a very interesting critique of Michael’s book.

However I came away with the impression that Susan Bayly has considerably overplayed her hand. In fact after reading the review I have formed a much improved impression of Michael’s book. Sure,sure some of the criticisms she makes must be valid (I have zero expertise of the subject or of the correct methodology in historical analysis) but some others seem tendentious or contrived.

The one point that does concern me, however, is the charge that Michael takes a static view of caste (Karava caste) evolution and fails to pay attention to the dynamics (changing nature) of the social, economic and identity remanufacture aspects of caste in society. I wonder if that charge is true. If correct, it is severe.

Kumar D

CC People: Please have the patience to read the review through to the end.

Dear Michael,

:-),

I mean, tut tut.

I think you really gave that poor girl the vapours.

Twas a time in the good ole days when Europeans obsessed by class and race could point fingers in horror at the barbaric customs of natives; Like caste for instance. But now, overcome with guilt for the sins of their great great great grand parents and the fact that Marxism has failed, matters like caste must be treated like the next door neighbours’ dirty little family secrets and tip toed around, exuding sympathy and understanding. If Uncle Claude has made little Mabel pregnant, one must take into account his childhood traumas and the fact that he takes her to McDonalds.

No more of Napier’s nonsense*. Just as with a number (though by no means all) whites in the Confederate States, a number of Indians including the highly educated, deeply resent outsiders expressing opinions on their “peculiar institution”. Caste riots in South India are clearly harmless bun fights and it would be most impolite to mention the bloody retaliations in Orissa and backward states like Bihar, to low castes daring to break out of their social confinements by conversion to other religions. Caste War? (faint faint).

Therefore if you are a Liberal [sic] white academic, when discussing these matters the acceptable tone is that of Pish Tush in “The Mikado”:

And I am right,

And you are right,

And all is right as right can be!

Clearly clueless about Sri Lanka, she judges your presentation as she would one on an area she is familiar with: India. If she was a respected expert on the social interactions of the Alaskan Inuit, naturally [sic] she would apply te same yardsticks for a study of the Sami People of Norway, on the scientific rationale that both groups are Mongoloid and use huskies.

But she has a point. As a down south boy brought up in a provincial town typical from Matara to Point Pedro, though unaffected by it because of your racial and social position, caste was like mosquitoes in the Mississippi Delta – all around you. You therefore speak as a Sri Lankan to Sri Lankans but addressing a far wider readership which has no such familiarity with the environment you are observing. In that context she is quite right in saying that you make unsubstantiated statements. A lot of what you consider as self-evident is anything but, to an alien audience. More than other Asians who would disgaree with you, I think your main opposition would come from the Western White PC Brigade who feel honour bound to make Malcolm X look like a Klansman.

Communication is about getting through to your audience. In an issue like this which as she accurately describes as a minefield, getting inside the minds of the protagonists is not enough, you need to penetrate the minds of your audience as well so as to give them an explanation which they can accept. For this I think you should first send your work for the reactions of a white liberal academic, preferably one whose views are differnt from your own, to highlight the chinks in your armour. These could then be addressed in footnotes in order to maintain the flow of your argument.

All the very best and rooting for you,

With respect,

Anoma.

(Addendum. See end re *)

Dear Michael,

:-),

I mean, tut tut.

I think you really gave that poor girl the vapours.

Twas a time in the good ole days when Europeans obsessed by class and race could point fingers in horror at the barbaric customs of natives; Like caste for instance. But now, overcome with guilt for the sins of their great great great grand parents and the fact that Marxism has failed, matters like caste must be treated like the next door neighbours’ dirty little family secrets and tip toed around, exuding sympathy and understanding. If Uncle Claude has made little Mabel pregnant, one must take into account his childhood traumas and the fact that he takes her to McDonalds.

No more of Napier’s nonsense*. Just as with a number (though by no means all) whites in the Confederate States, a number of Indians including the highly educated, deeply resent outsiders expressing opinions on their “peculiar institution”. Caste riots in South India are clearly harmless bun fights and it would be most impolite to mention the bloody retaliations in Orissa and backward states like Bihar, to low castes daring to break out of their social confinements by conversion to other religions. Caste War? (faint faint).

Therefore if you are a Liberal [sic] white academic, when discussing these matters the acceptable tone is that of Pish Tush in “The Mikado”:

And I am right,

And you are right,

And all is right as right can be!

Clearly clueless about Sri Lanka, she judges your presentation as she would one on an area she is familiar with: India. If she was a respected expert on the social interactions of the Alaskan Inuit, naturally [sic] she would apply te same yardsticks for a study of the Sami People of Norway, on the scientific rationale that both groups are Mongoloid and use huskies.

But she has a point. As a down south boy brought up in a provincial town typical from Matara to Point Pedro, though unaffected by it because of your racial and social position, caste was like mosquitoes in the Mississippi Delta – all around you. You therefore speak as a Sri Lankan to Sri Lankans but addressing a far wider readership which has no such familiarity with the environment you are observing. In that context she is quite right in saying that you make unsubstantiated statements. A lot of what you consider as self-evident is anything but, to an alien audience. More than other Asians who would disgaree with you, I think your main opposition would come from the Western White PC Brigade who feel honour bound to make Malcolm X look like a Klansman.

Communication is about getting through to your audience. In an issue like this which as she accurately describes as a minefield, getting inside the minds of the protagonists is not enough, you need to penetrate the minds of your audience as well so as to give them an explanation which they can accept. For this I think you should first send your work for the reactions of a white liberal academic, preferably one whose views are differnt from your own, to highlight the chinks in your armour. These could then be addressed in footnotes in order to maintain the flow of your argument.

All the very best and rooting for you,

With respect,

Anoma.

(* “Be it so. This burning of widows is your custom; prepare the funeral pile. But my nation has also a custom. When men burn women alive we hang them, and confiscate all their property. My carpenters shall therefore erect gibbets on which to hang all concerned when the widow is consumed. Let us all act according to national customs.[To Hindu priests complaining to him about the prohibition of Sati religious funeral practice of burning widows alive on her husband’s funeral pyre.]”)