Shanie in Notebook of a Nobody

Courtesy of the Island, 27 November 2010

Yasmine Gooneratne wrote the poem ‘Yasodhara’ on a different theme. But the last stanza above perhaps reflects the mind and mood of many Yasodharas of our country at this time. Rizana Nafeek languishes in a death row in Saudi Arabia betrayed by life and hoping, like millions around the world, that she will be allowed to return home to her family and friends in the impoverished village of Mutur. And within our own country, there are thousands of women, widowed by a tragic war, who suffer in silence with their shaken gaze leaping from emptiness to emptiness.

Yasmine Gooneratne wrote the poem ‘Yasodhara’ on a different theme. But the last stanza above perhaps reflects the mind and mood of many Yasodharas of our country at this time. Rizana Nafeek languishes in a death row in Saudi Arabia betrayed by life and hoping, like millions around the world, that she will be allowed to return home to her family and friends in the impoverished village of Mutur. And within our own country, there are thousands of women, widowed by a tragic war, who suffer in silence with their shaken gaze leaping from emptiness to emptiness.

Rizana Nafeek

In the case of Rizana Nafeek, many appeals have been made to the King of Saudi Arabia to pardon this young woman. One small step has been taken in this process. Her father, engaged in collecting wood from the forests and selling them as firewood for his livelihood, is the sole bread-winner of this family of six. Rizana’s three younger siblings are of school-going age. Indeed, Rizana herself was attending school when someone arranged a passport falsifying her age to enable her to obtain employment in Saudi Arabia. She was as vulnerable as the many abused child soldiers in our own country when she found herself as a housemaid in the remote village of Ad Dawadami in central Arabia. Her employers spoke no Tamil the only language she spoke. We already know the circumstances under which the infant who was left in her sole custody died. But, is was good to be reminded by Suriya Wickremesinghe of the insufficient attention that had been paid to the social and economic background of the family of this young girl who has been charged and convicted of murder by the Saidi judicial system. Suriya Wickremesinghe’s comments need to be re-stated: “One wonders whether enough attention has been given to the likelihood that Rizana was in a seriously traumatized state herself? Bad enough that she was the eldest child of a family living in the direst poverty in Mutur, a small multi-ethnic town in the Trincomalee District of North East Sri Lanka. Their sole income was from wood-collecting in the forest. Do we realize that this under-age girl was sent abroad (on a forged birth certificate) less than five months after the tsunami that caused particularly appalling devastation on our east coast? How far has it sunk into us that she had suffered living in a war torn area all her life? Do we have any conception of the extent to which the society in which she grew up has been continuously ravaged by decades of armed conflict? How this started even before she was born? Have we thought of what it must have been like for her to arrive in Saudi Arabia, in a totally alien environment, unable to speak or understand the language, in a desperate effort to help her destitute parents and three younger siblings? Have we been sufficiently conscious of all these extra factors, which require heightened sympathy for her and her desperate family?”

The War Widows

Rizana’s case is similar to the many thousands of young women who have been widowed as a result of the recent civil war in our country. These include widows of security force personnel killed in the war, of LTTE cadres similarly killed and of innocent civilians caught in the cross-fire. In almost all cases, the widowed are from deprived homes as Rizana was. Many joined the security forces because of the impoverished circumstances of their lives. The family needed an income to survive. All talk of fighting to save the motherland is largely rhetoric, though there may have been a marginal ideological basis in the case of some recruits. For the vast majority, it was dire economic circumstances that forced many young men from our villages to enlist. This is also the reason why so many young soldiers now serving in the Vanni are able to empathise with the re-settled displaced persons who find themselves in similar deprived economic circumstances.

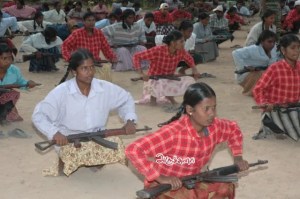

In the case of the LTTE cadres too, many of them were conscripts who were forced into the war. They were not volunteers who joined the LTTE for ideological reasons to fight against “the enemy”. Most of them perhaps had some sympathy for the Tamil nationalist cause as many in middle class had. But those who were conscripted into the LTTE army had no choice in the matter. The more affluent found means of avoiding conscription but it was the young boys and girls from the poorer homes who were forced into fighting against their will.

Photos of LTTE mobilisation and training of a civilan militia in 2008 — phots parachuted into my email butut presumably extracted from pro-Tiger web sites

Then there are the widows of civilians who have died. They were civilians caught in the cross-fire who found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time. How long have we to endure the fiction that no civilians died during the final weeks of the war. Certainly, there is every reason to believe that the security forces did not deliberately target civilians; but because the LTTE cadres in the limited space of the safety zones were mingling with the civilians, many have witnessed civilian deaths in large numbers. The government must realize that it will further reconciliation and its own credibility if this is acknowledged. Surely, no one can be expected to believe that there were zero civilian casualties in a war of this nature?

Tamil refugees at rear of battle lines after release from the last redoubt, probably taken by the Defence Ministry in late April or early May 2009 — Photo from Sunday Times, May 2009

This columnist has met and spoken to young widows. Many of them are still in their twenties and yet with two to four children bring up as a single parent. Family elders help to look after the children while the widows seek to earn an honest livelihood in whatever way possible. School education for the children remains a problem, as also health care. A few weeks ago, we quoted from a study by Prof. Daya Somasundaram of stories related by children caught up in the war. Prof. Somasundaram writes that in many countries in the world trying to recover from internal, civil conflict, a well-known method was to promote a ‘healing of memories’ towards national reconciliation; when people come to realize and understand what had happened by reading and finding out about the past through narratives from different perspectives, they will then be in a better position to reconcile, forgive and reform relationships on the basis of mutual understanding. Sharing of stories creates empathy and brings relief. In many countries of South America that went through periods of civil war and repression, testimonies and stories of survivors were collected and published as Nunca Mas (never again) reports. The Nunca Mas stories were photocopied for circulation or published as cheap paperbacks in book stalls and street corners that sold out quickly in their hundreds of thousands. The publication of these testimonies completely changed the public awareness and brought about a radical opening to public discourse and eventually, social transformation in those countries.

The Narratives of the Survivors

It is with this in mind that Prof Somsundaram has collated and put down in his study narratives from a variety of survivors of the Eelam War. He apologises that he had collected the narratives only from the Vanni during his work which has already been published in a medical journal as part of a research study. He says he is trying to obtain narratives from other perspectives, such as soldiers. We quote two stories by two war widows from Somsundaram’s study.

1. “A 60-year-old woman was mumbling: I have three married children with 10 grand children. We were displaced 14 times from our home. Food was difficult. Rice was 250, chilli powder 22, coconut 250. Rice and dhal was food. We could not take it anymore. So we tried to leave. When we were in a trappan shack, a shell fell killing my husband, son in law, grandchildren, all together 8 people died then and there. Daughter and a grandchild were injured. So I was sent as a helper. I do not know what has happened to the rest. We have to beg even for the clothes we wear. We did not even bury the dead. Do we need a life like this? I could have died with them. Why did I come here? Have I to go on living? Those who should live have gone. What is there for me anymore….”

2. “I was 27 years old living happily with my husband and two small children in our native village. Husband was farmer with a lot of land. We were able to find enough food. The war situation made us move 3 to 4 times. We were heading for a safe place when there was heavy shelling. I do not know what happened next. When I opened my eyes I was in hospital. My mother and daughter were by my side. I was without a leg and fingers. Daughter is also injured. I learned that my husband and 2 year old daughter had passed away. I am 7 months pregnant. I do not know how I am going to give birth to this child and then bring it up. I am troubled. There are no relations here. How is our future going to be?”

First makeshift clinic at Manik Farm IDP detention camp, Zone 1 and 2 –Pics by Dr Donnie Woodyard

![DSC_1030[1]--setting up field hospital](https://i0.wp.com/thuppahis.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/dsc_10301-setting-up-field-hospital.jpg?resize=300%2C200) Setting up field hospital in mid-April 2009 — structures designed by Donnie and construction by a private firm on the books of the Presidential Task Force

Setting up field hospital in mid-April 2009 — structures designed by Donnie and construction by a private firm on the books of the Presidential Task Force

Starting from scratch in receiving IDPs at Manik Farm — military, civilian and INGO and NGO personnel assemble to take on the enormous task of establishing huts, medical centres, kithcnes and toilets etc in ‘ground zero’ conditions

Presented below are images taken by Michael Roberts, one year later in early June 2010 when there were only about 50,000 left in Manik Farm and when there was less congestion

Field hospital in Zone 2 -set up in April and initially having dirt floors till the Presidential Task Force organised the insertion of concrete floors in June 2009.

Tuk-tuk ambulance – an inovation designed by Donnie Woodyard and sponsored by USAID and UMCOR

Justice for the Deprived

Each war widow will have a similar tragic tale to relate. It was the same with the two southern insurgencies. And in all cases, it was the poor from a deprived social and economic background who suffered most. Apart from the war widows, there are others who have been temporarily “widowed” due to emergency regulations. Rizana Nafeek and her family await with hope for her release. So also many families in our country await with hope for the release of their loved ones held in custody under emergency regulations and the dreaded Prevention of Terrorism Act. Some of them have been held in custody for years without any charges being framed against them.

Over twenty years ago, Jayatilleke de Silva, the present Editor of the Ceylon Daily News, was arrested and remanded under the emergency regulations and Prevention of Terrorism Act basically for daring to dissent from the then J R Jayewardene government. Last year, his story was published in a volume analysing the PTA. He was incarcerated for a little under 3 years and freed by the High Court of Colombo in 1988 on a Nolle Proseequi filed by the Attorney General. He says that after two decades, it was possible for him to write dispassionately on his experience. ‘Yet such writing cannot convey the physical and psychological impact on its victim,…The trauma and the entire gamut of debilitating factors have to be experienced to feel the full ferocity of the PTA. In other words, for a full comprehension of the PTA, its venom has to be tasted in person.”

We trust the stories of Rizana Nafeek, of the war widows and of Jayatilleke de Silva will awaken in us a spark of conscience to demand justice for the socially, politically and economically deprived in our society.

NB: other than the first photograph, which accomapanied the article and was taken from the Island, the others are impositions by the Editor of this site in an attempt to provide the context in a manner that embellishes motifs referred to in the article.

![DSC_1035[1]-first makeshift clinic](https://i0.wp.com/thuppahis.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/dsc_10351-first-makeshift-clinic.jpg?resize=300%2C199)

![DSC_1029[1]--starting from scratch](https://i0.wp.com/thuppahis.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/dsc_10291-starting-from-scratch.jpg?resize=300%2C200)